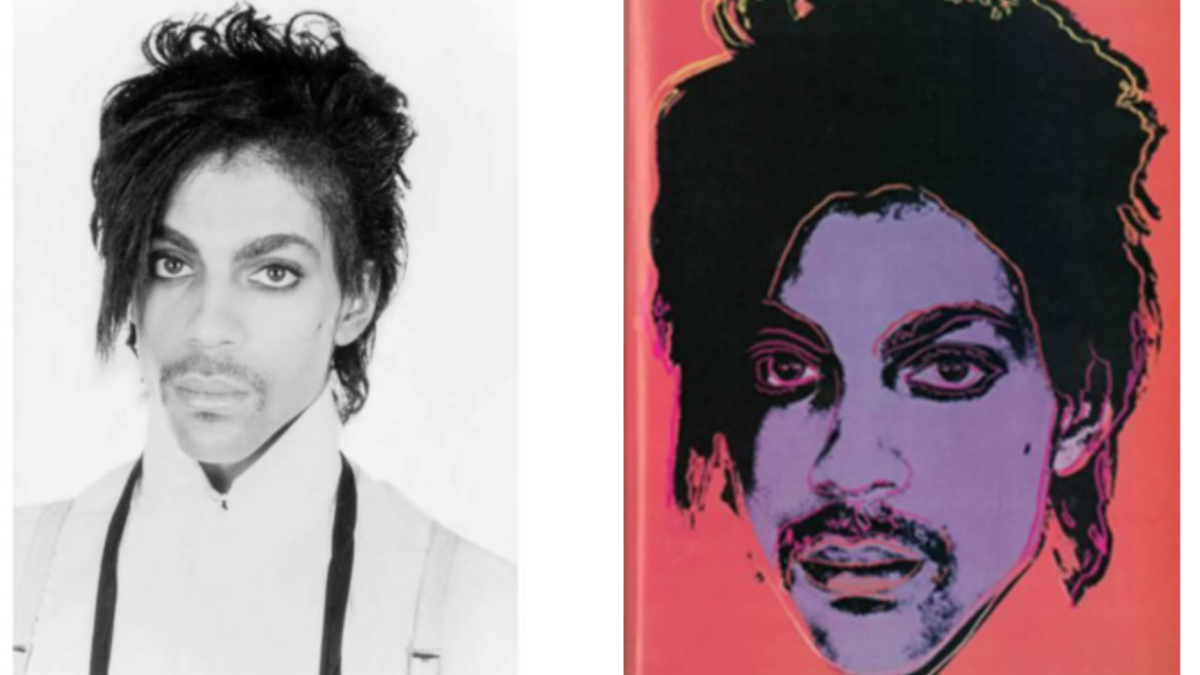

In 1981 the photographer Lynn Goldsmith took a portrait of Prince. He sits alone on a white background, carrying a clean expression with a glint of sunshine in his eyes. In 1984 Andy Warhol used that picture to create artwork. Warhol altered the picture, adjusting the angle of Prince’s face, layering on swaths of shade, darkening the sides, and including hand-drawn outlines and different particulars in a sequence of 16 silkscreen prints.

40 years later, the art work is on the middle of a Supreme Court case that might change the course of American artwork, copyright legislation, and even the state of the web. The query is whether or not Warhol’s work was truthful use, or if he violated Goldsmith’s copyright. In oral arguments on Wednesday, the Court wrestled with the finer factors of the problem, and to place it mildly, it’s fairly difficult.

Did Warhol create a wholly new murals, or was it only a spinoff reinterpretation of Goldsmith’s picture? If the artwork is discovered to be spinoff, the Warhol Foundation will owe Goldsmith tens of millions in charges, royalties, and maybe further damages. But the implications of the Supreme Court’s impending resolution are a a lot greater deal than just a few million {dollars}.

Goldsmith argues that siding in opposition to her would pave the best way for artists to have their work appropriated with out compensation, which she says would decimate the sphere of images. On the opposite aspect, a ruling in favor of Goldsmith, “would make it illegal for artists, museums, galleries, and collectors to display, sell, profit from, maybe even possess a significant quantity of works,” stated Roman Martinez, a lawyer for the Warhol Foundation. “It would also chill the creation of new art by established and up-and-coming artists alike.”

The aftershocks may unfold far past the artwork world, too. The query of truthful use is a basic concern on the web, social media platforms specifically. For instance, YouTube has copyright algorithms that scan each video. If they detect footage or music that YouTube doesn’t have a license to make use of, the video will get flagged, suspended, or eliminated. This form of algorithm is designed to err on the aspect of warning, and if the principles about truthful use turn into stricter, platforms may get much more heavy-handed in their choices about eradicating content material. Imagine filters that convey down the banhammer on any video that has a visible similarity to copyrighted materials. Sure, that might be an excessive consequence, however that is an excessive case. We’re speaking about legally erasing the legacy of probably the most well-known artist of the twentieth century.

G/O Media could get a fee

It’s an previous cliche that there’s no such factor as utterly unique artwork. Every piece owes one thing to all of the artwork that got here earlier than it. The extra you’re borrowing from different artists although, the extra unique you must be.

You don’t must pay the unique artist if it’s truthful use, which is set based mostly on four factors: the aim you’re utilizing it for, the character of the artwork, how considerably you used the unique work, and the way your new artwork impacts the marketplace for the unique. The attorneys, on this case, centered on the primary and fourth elements, objective and the market.

If your objective is to say one thing humorous about an present piece of artwork, you’re most likely within the clear. The Court beforehand dominated that 2 Live Crew’s take on Roy Orbison’s 1964 basic Pretty Woman was truthful use as a result of it’s a parody that considerably “transforms” the unique work.

The Warhol Foundation argues that its appropriating prints remodel the {photograph}, too, as a result of they’ve a distinct which means and message. The unique picture was simply purported to be an image of Prince, however Warhol’s work was meant to be an announcement about “the dehumanizing effects of celebrity culture in America,” Martinez stated.

Chief Justice John Roberts appeared to agree that form of transformation was potential, however he voiced considerations. What in case you simply “put a little a smile on his face and say, this is a new message,” Roberts requested. “The message is, ‘Prince can be happy. Prince should be happy.’ Is that enough of a transformation?”

Several Justices appeared uncomfortable with the duty of answering that form of query. So too was a decrease courtroom. The Second Circuit Court determined in favor of Goldsmith and threw out the entire query of the which means and message of a murals, saying that judges “should not assume the role of art critic.” The Second Circuit stated as an alternative that the case ought to concentrate on the “character” of the artwork, which primarily means how aesthetically related the 2 items are, ruling that Warhol and Goldsmith’s artworks had been an excessive amount of alike for this to be a case of truthful use.

Neither aspect appeared fully proud of that ruling. Even Goldsmith’s representatives agreed that the 2nd Circuit was mistaken, conceding that which means and message are points that the authorized system ought to deal with.

To be truthful use, the brand new artwork doesn’t simply must be transformative, it needs to be totally different sufficient that it doesn’t compete as an alternative choice to the unique work within the artwork market. That may pose an issue for the Warhol Foundation. Goldsmith’s picture was taken for an article about Prince for Newsweek, and Warhol’s piece was utilized in an article about Prince for Vanity Fair.

“The difficulty of this case is that this particular image is being used, arguably, maybe for the same purpose, to identify an individual in a magazine in a commercial setting,” stated Justice Neil Gorsuch.

Justine Sonia Sotomayor appeared to agree, however Justice Roberts challenged the concept. “It’s a different style. It’s a different purpose. One is a commentary on modern society. The other is to show what Prince looks like,” Justice Roberts stated.

The arguments had been unusually lighthearted for the Court, with each attorneys and Justices cracking jokes concerning the world of artwork and popular culture. A chuckling Justice Clarence Thomas made a degree to say he was a fan of Prince, a minimum of within the 80s, whereas Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s feedback recommended a passion for the “Lord of The Rings.”

But the Court’s resolution may have critical implications. A broad ruling in favor of the Warhol Foundation may theoretically make it simpler to steal or make liberal use of artists’ work. During the trial, the query of film diversifications of books bought plenty of consideration. Justice Sotomayor identified that filmmakers reinterpret plots, add characters and dialogue, and make different modifications that may very well be thought of transformative, however nobody argues that you simply shouldn’t must pay an writer whenever you flip their e book right into a film.

As Goldsmith’s lawyer Lisa Blatt put it, the mistaken ruling may imply “anyone could turn Darth Vader into a hero or spin-off ‘All In The Family’ into ‘The Jeffersons’ without paying the creators a dime.”

On the opposite hand, a slender ruling in favor of Goldsmith may have big repercussions for the artwork world. The estates of pop artwork icons Robert Rauschenberg and Roy Lichtenstein joined the Brooklyn Museum in an amicus transient, telling the courtroom upholding the 2nd Circuit’s resolution, would “impose a deep chill on artistic progress, as creative appropriation of existing images has been a staple of artistic development for centuries.”

#Supreme #Court #Hears #Warhol #Case #Fair

https://gizmodo.com/the-supreme-court-could-end-fair-use-as-we-know-it-1849652186